Friday, November 16, 2012

A History of Female Superheroes

From the beginning of superhero comic book history, women were usually delegated to supporting roles, and were usually portrayed as either career women, romance-story heroines, or comedic teenagers.

This all began to change in the 1940s, as part of the growing women's empowerment of the time. The first known female superhero is Fantomah, a jungle woman with super natural powers, who debuted in Fiction House's Jungle Comics #2 on February 1940, made minor minor appearances in a few comic before disappearing, eventually lapsed into public domain and has since made several appearances in modern comics with the rediscovery of her first female superhero status, most recently in Hack/Slash. 1940 saw the arrival of several female superheros, including the original Black Widow, the first costume superheroine, Invisible Scarlet O'Neil, the first comic strip superheroine, and Nelvana of the Northern Lights, the first superheroine to headline a comic book. Femme fatales started becoming common archetypes. Wonder Woman, the most famous superheroine, soon made her debut in All Star Comics #8, published January 1942 and is frequently used as a feminist symbol, usually in a positive fashion.

Things changed in the 1950s with the implementation of the Comics Code, which placed certain restrictions on things like the portrayal of women in comics, like DC's In-house Editorial Policy of "The inclusion of females in stories is specifically discouraged. Women, when used in plot structure, should be secondary in importance, and should be drawn realistically, without exaggeration of feminine physical qualities". This resulted in women being relegated to supporting roles for some time, but writers began pushing against this by creating or reintroducing superheroine versions of popular superheroes, like Supergirl, Batwoman and Batgirl.

As the 50s changed into the 60s and second-wave feminism started, superheroines became more predominate, becoming equal (albeit gradually and often outnumbered) members of superteams, such as The Fantastic Four's Invisible Girl's developing the additional ability to generate force fields and transitioning from a damsel in distress to a confident second in command before changing her name to Invisible Woman and the increase in more prominent women on the X-Men. While at first often the "token female member", eventually they stated becoming the leaders of superteams, such as Storm becoming the leader of the X-Men. 1975 saw the reintroduction of the X-Men to the public after a five year hiatus, with the regular series Uncanny X-Men being written by Chris Claremont, whose 16 year run as the book's writer, in addition to other comics, was lauded for things like the creation of several strong female characters, including Shadowcat, and Mystique, and growing existing superheroines like Storm and Jean Grey. Claremont's depiction of smart, powerful, capable and multifaceted superheroines is credited for reinvigorated the portrayal of women in comic.

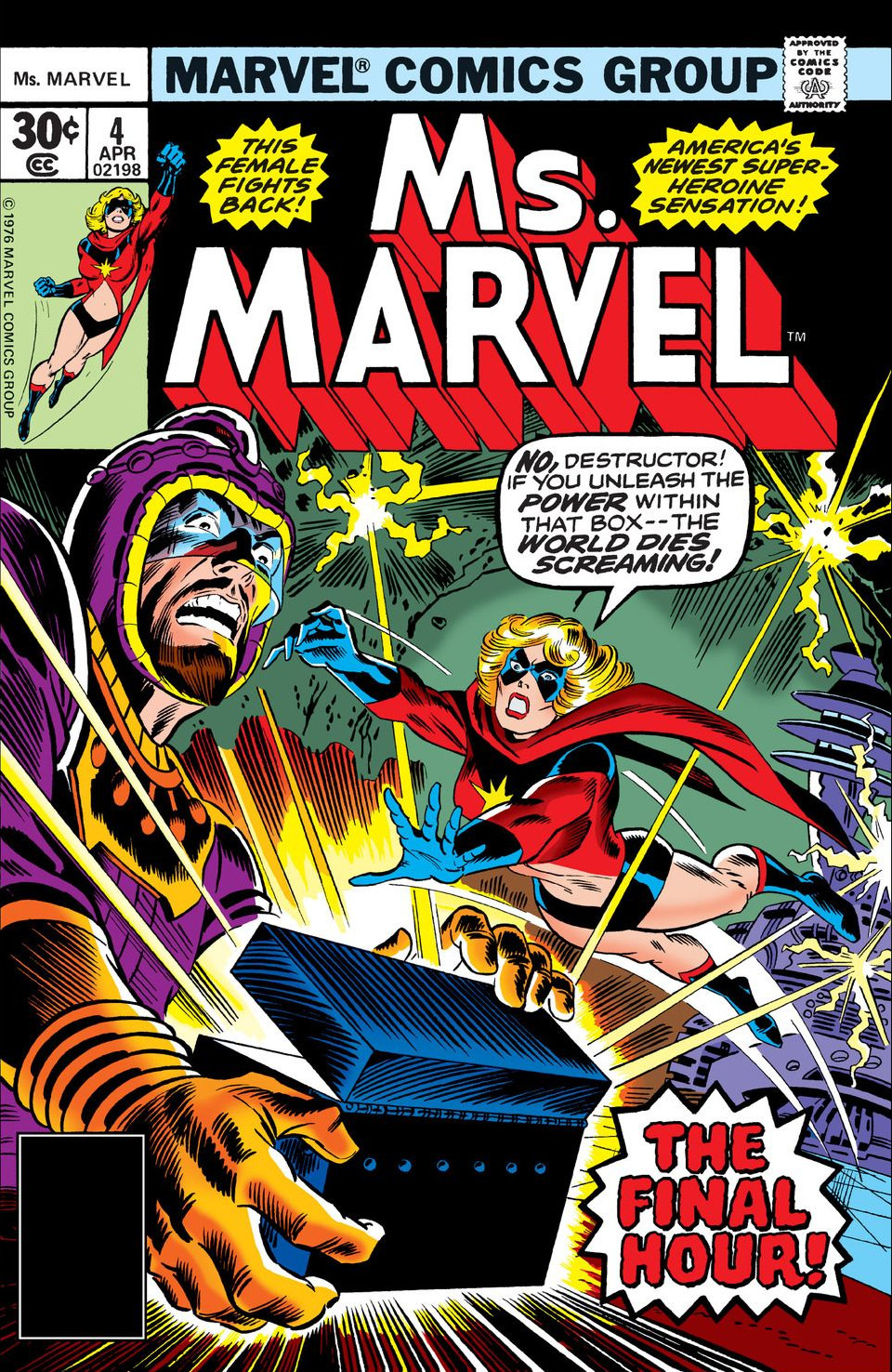

Feminism became a recurring subject in comic books, both positive, like the feminist solidarity symbol Ms. Marvel with her women's magazine editor day job and tagline "This Female Fights Back!", and negative, like the feminist "parody" supervillian Man-Killer. Superheroines saw a significant increase in their own titles, with some comic books like Spider-Girl becoming major sellers. The 90s saw an increase in more sexually open (and sexually explicit) comics as LGTB issues became story topics and underground and alternative comics grew in popularity with characters like Tank Girl. The rise of the internet allowed people to come together and re-examine past comics, and sites like Women in Refrigerators, which collected incidents of discrimination against women in comics and seek to analyze why these plot devices are used disproportionately on female characters, were created and incidents of women being portrayed as sexual objects are quickly reported and derided, such as the Mary Jane Laundry Statue or the recent Sexpot Starfire Controversy. Because of the attention these kinds of incidents have gathered depictions of women as stereotypes, sexual objects and victims of brutality has decreased in recent years.

Given that the audience for superhero comic books was primarily male until recently, female characters were designed to be targeted towards the male demographic. Despite the number of female superheroes created few have had significant stand alone success. It has long been debated if the perceived lack of female readership was due to male writers being uncomfortable or unable to write for or about women or if they are afraid that trying to appeal to women will lose them male interest. Some have said that women in general have a lack of interest in comics, but the rising number of women artists and writers, especially outside the superhero genre, suggests that's not the case. Whatever the reason, the growing trend of empowered and realistically portrayed women and superheroines is a positive sign for the industry, even if there are occasions where people in the industry lapse into misogynistic mindsets.

Labels:

Chris Claremont,

Fantomah,

Feminism,

History,

Invisible Woman,

Ms. Marvel,

Nelvana of the Northern Lights,

Shadowcat,

Spider-Girl,

Starfire,

Storm,

Superheroines,

Tank Girl,

Women's Rights,

Wonder Woman

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

One frustration is that male comic book readers tend to be just as feminist and just as offended by sexism as female comic book readers.

ReplyDeleteSo a lot of the female superhero characters fail not only because their grotesquely oversexualized bodies and distastefully shallow personalities offend most female readers but also because they offend most male readers.